Lithography works because of the mutual repulsion of oil and water. The image is drawn on the surface of the print plate with a fat or oil-based medium (hydrophobic) such as a wax crayon, which may be pigmented to make the drawing visible. A wide range of oil-based media is available, but the durability of the image on the stone depends on the lipid content of the material being used, and its ability to withstand water and acid. After the drawing of the image, an aqueous solution of gum arabic, weakly acidified with nitric acid is applied to the stone. The function of this solution is to create a hydrophilic layer of calcium nitrate salt and gum arabic on all non-image surfaces.[1] The gum solution penetrates into the pores of the stone, completely surrounding the original image with a hydrophilic layer that will not accept the printing ink. Using lithographic turpentine, the printer then removes any excess of the greasy drawing material, but a hydrophobic molecular film of it remains tightly bonded to the surface of the stone, rejecting the gum arabic and water, but ready to accept the oily ink.

When printing, the stone is kept wet with water. The water is naturally attracted to the layer of gum and salt created by the acid wash. Printing ink based on drying oils such as linseed oil and varnish loaded with pigment is then rolled over the surface. The water repels the greasy ink but the hydrophobic areas left by the original drawing material accept it. When the hydrophobic image is loaded with ink, the stone and paper are run through a press that applies even pressure over the surface, transferring the ink to the paper and off the stone.

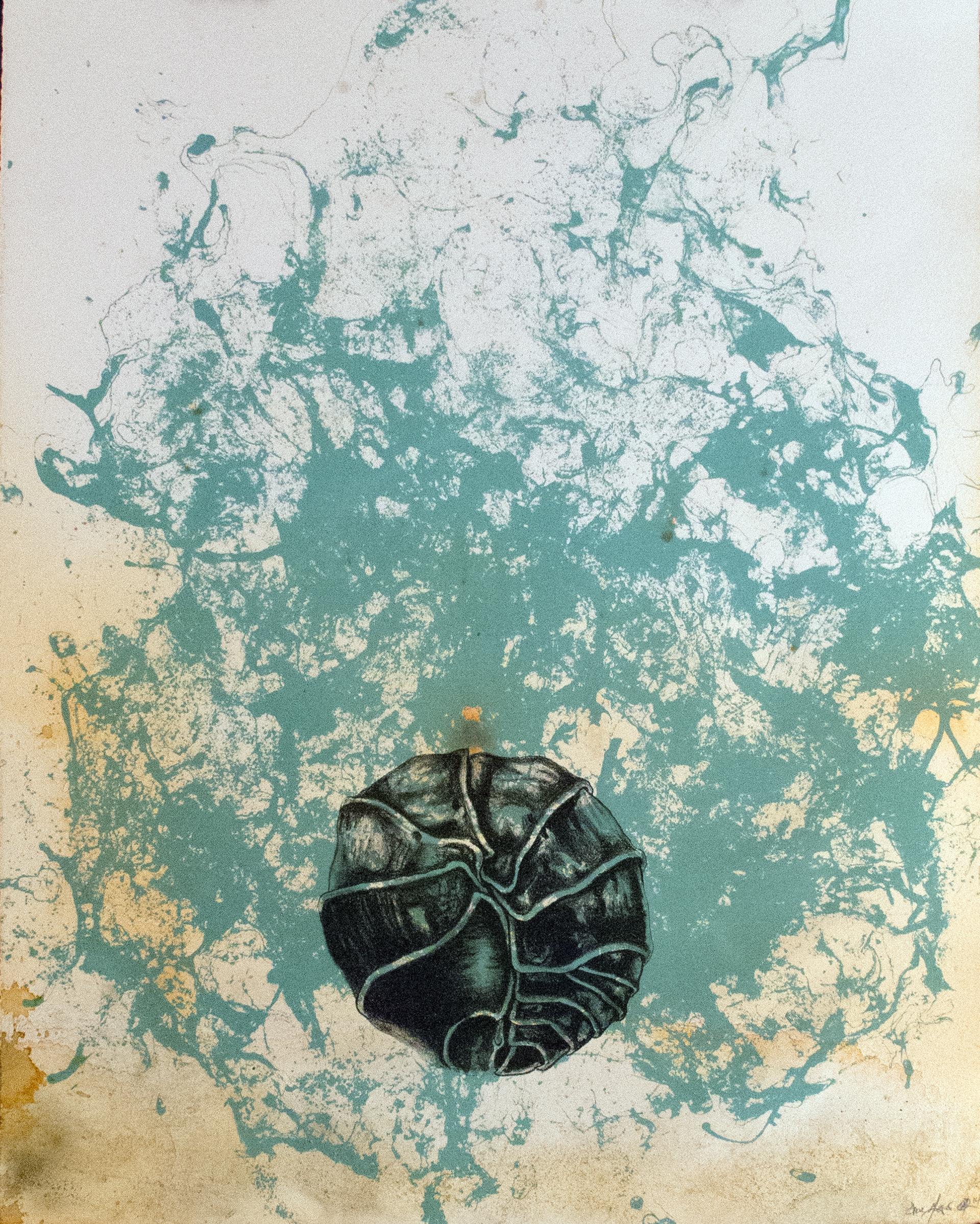

Senefelder had experimented during the early 19th century with multicolor lithography; in his 1819 book, he predicted that the process would eventually be perfected and used to reproduce paintings.[3] Multi-color printing was introduced by a new process developed by Godefroy Engelmann (France) in 1837 known as chromolithography.[3] A separate stone was used for each color, and a print went through the press separately for each stone. The main challenge was to keep the images aligned (in register). This method lent itself to images consisting of large areas of flat color, and resulted in the characteristic poster designs of this period.

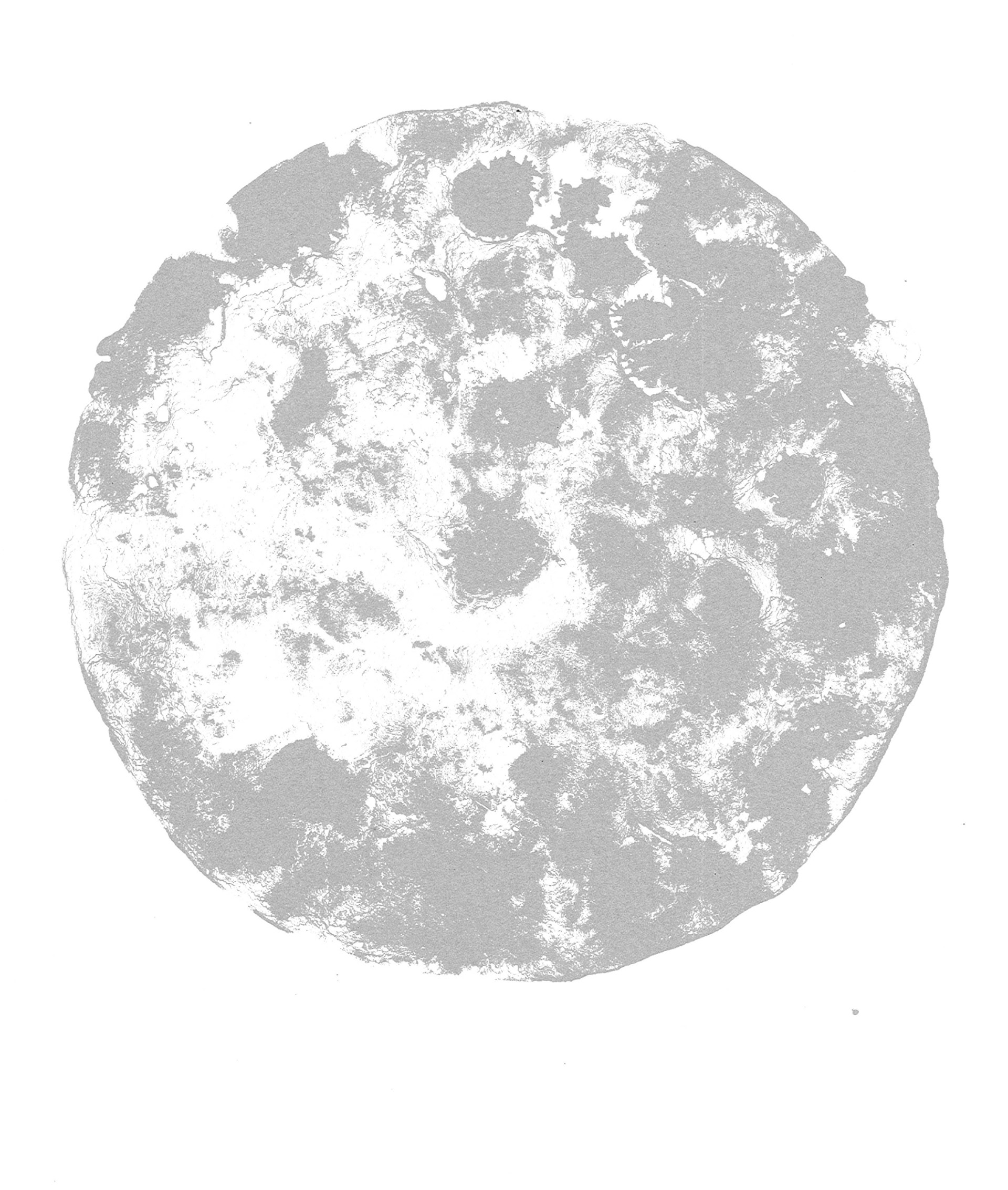

"Lithography, or printing from soft stone, largely took the place of engraving in the production of English commercial maps after about 1852. It was a quick, cheap process and had been used to print British army maps during the Peninsular War. Most of the commercial maps of the second half of the 19th century were lithographed and unattractive, though accurate enough.